Viewing Renoir: A Different Kind of Challenge

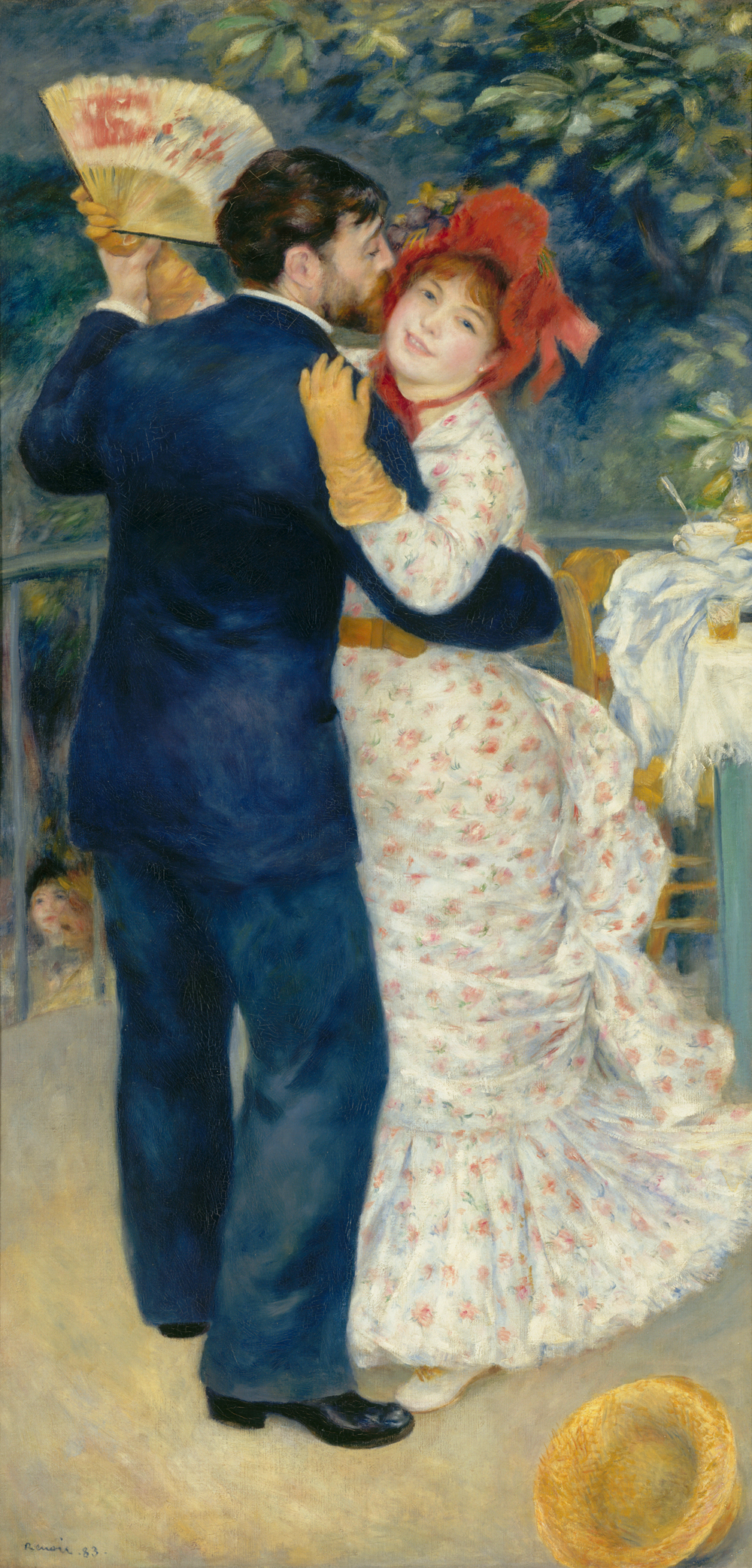

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: “Dance in the Country or Dancers (Bougival),” 1883 | © Paris, Musée d’Orsay, RF 1979 64

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

It can be fun to go to an exhibition by an artist you know little about or, in some cases, don’t like much. This is why I’m looking forward to “Renoir: The Painter and his Models” at the magnificent Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, beginning September 22. I want to challenge my ignorance and preconceptions.

Spanning 70 compositions, this is said to be the first comprehensive and representative showing of Renoir’s work in Hungary. The exhibition is organized in cooperation with Paris’ Musée d’Orsay and Musée de l’Orangerie. Pieces have been loaned from more than 20 public collections and focus on his depiction of figures.

Featuring masterpieces such as “The Swing” and “Dance in the Country,” the exhibition is arranged chronologically and thematically around portraits, modern life, and nudes.

The portraits show how Renoir’s approach changed depending on whether he was painting his family, friends or clients. Modern life explores his interest in what fashionable Paris did for fun. The nudes section traces his move away from just being interested in the play of light and shadow on bodies to unified, painterly solidity.

Renoir’s last masterpiece, “The Bathers,” dating from 1919, has a section to itself. I’ve never seen this painting. I’m keen to experience all that intense color in the flesh, as it were.

Easily one of the most famous Impressionists, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), was one of the founders of a movement that revolutionized painting at the time.

Impressionism was about trying to record the shifting effects of light. It was partly a response to science discovering that matter wasn’t solid and also to photography, which seemed to render realist painting irrelevant.

It’s hard to imagine the Impressionists as radical, but they were. They broke the rule of academic painting by putting colors before lines and contours, painted realistic scenes of modern life and often worked outside. Comprised of short brush strokes, their style aimed to reproduce intense vibrating color.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: “The Swing,” 1876 | © Paris, Musée d’Orsay, RF 2738

Abstract Pathway

Impressionism began the process that led to the breakdown of interest in painting “reality” accurately and, ultimately, to abstract painting.

Aged 40, inspired by Renaissance and French Rococo masters, Renoir moved away from Impressionism. He created a new, modern tradition as a “painter of figures,” inspiring Picasso and Matisse with his dedication to experimentation, innovation, and sheer hard work.

It has to be said that Renoir’s influence in Hungary is not that great as Anna Zsófia Kovacs, head of the museum’s Department of Fine Art After 1800, tells me.

“I don’t think that many Hungarian artists were directly and deeply inspired by Renoir. Most of them discovered him and Impressionism in general only after the turn of the century,” she says. “The most obvious parallels are with the works of István Csók. János Vaszary has a few paintings exploring similar themes and techniques as the Impressionists, notably ‘Breakfast in the Open Air’ (1907).”

Researching this article, I asked a painter friend of mine what he thought of Renoir.

“I’ve always had an aversion to old Auguste because of the overly sentimental subject matter,” he said. “But when I see him crippled with arthritis in old age, painting with his brushes taped to his hands because he’s lost his grip, I’m impressed.”

Whatever you think of Renoir’s work, his sheer persistence has to be admired. He started out as a porcelain painter earning money to support his family, developed his talent by copying artworks in the Louvre and, aged 21, enrolled in the prestigious École de Beaux-Arts.

Next, he began doing portraits while painting with his contemporary Claude Monet in the open air, going against the academic tradition of painting inside. Returning from serving in the Franco-Prussian war in 1871, Renoir built up a successful portraiture business.

Change of Approach

At 40, an age when he could have been expected to rest on his laurels a little, Renoir changed his approach as he began exploring classical painting. In 1883, on holiday in the English Channel island of Guernsey, he painted a series of landscapes that seemed to return to his Impressionistic style. In the 1890s, he concentrated on painting his family and scenes from what, by now, appeared to be a bourgeois French life.

In 1907, suffering from arthritis, Renoir moved to Cagnes-sur-Mer on the French Riviera. It was here that he painted “The Bathers,” an artwork that gets odder the more you look at it, and was completed the year Renoir died.

In recent years, Renoir’s once transcendent reputation has taken a bit of a beating. On the Art UK website, in a piece titled “Revered or Reviled: Do We Still Like Renoir?” posted on December 2, 2019, Lydia Figes writes: “The artist’s brushstrokes, once considered expressive, are now viewed as ‘ponderous staginess,’ according to the New York Times art critic Roberta Smith. His sentimental subject matters, once deemed charming, now nauseate people with their syrupy, saccharine qualities.”

Figes goes on to mention “Max Geller’s ‘Renoir Sucks at Painting,’ an Instagram account which snowballed into a quasi-serious protest movement named ‘God Hates Renoir.’ In 2015, anti-Renoir ‘activists’ could be seen standing outside American national museums to protest the artist’s inclusion in their collections.”

There are several reasons why some now detest Renoir. Apart from criticism of his style and subject matter, which ignore the context in which he painted, hostility comes from those who regard his nudes as voyeuristic and politically incorrect.

Leaving aside the question of whether it’s right or wrong for men to paint nude women, I’d say that the problem some people have with Renoir is that his paintings appear to be only about pleasure. But as the man himself said, “Why shouldn’t art be pretty? There are enough unpleasant things in the world.”

In these dark and troubled times, I’m ready for a bit of provocative pleasure.

“Renoir: The Painter and His Models” is at Budapest’s Museum of Fine Arts (Dózsa György út 41, Budapest 1146) from September 22 to January 7, 2024. A standard weekday ticket is HUF 5,200, and the museum is open Tuesday to Sunday: 10 a.m.-6 p.m.

This article was first published in the Budapest Business Journal print issue of September 8, 2023.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.

.png)

.png)