30 Years of Freedom: The 1st Free Elections and the Formation of the Antal Government

Antall family archives

Thirty years ago, on May 23, 1990, a few weeks after the formation of the first freely elected Parliament in 43 years, the government of József Antall took the oath of office. With this, Hungary reached a huge milestone along its path of regime change.

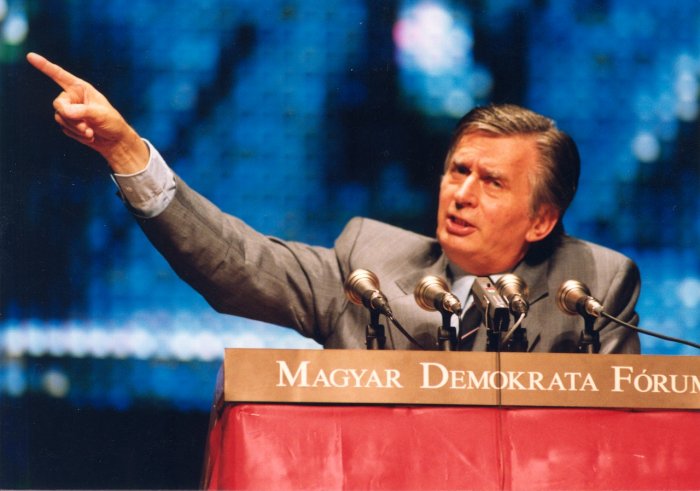

Hungarian Prime Minister József Antall giving a speech during a campaign event in the 1990 Hungarian municipal elections. The photo was taken by Péter Antall. From the Antall-család archívum (Antall family archives).

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Hungary transitioned from a one-party, socialist regime to a multi-party democratic system in 1989-1990. The processes of change, however, had started well before, and in parallel with the erosion of the communism.

Despite the best efforts of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP), by the end of the decade the one-party system was badly cracked. In 1989, there was so much pressure on the government that it finally bowed to the opposing forces and split into two. The 1949 Constitution (more properly Act XX of 1949 on the Constitution of the Republic of Hungary) was modified and the Hungarian Republic was proclaimed on October 23, 1989.

Six months later, the first pluralist elections were held in Hungary, and a new government was formed. The run-up to the elections saw a series of events including the formation of the Opposition Roundtable, formed by intellectual groups and movements. Among the leading parties was the right of center (although it was initially a fairly broad church) Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF) which, by October 1989, had become Hungary’s largest opposition party.

The Forum was led by the Budapest-born József Antall, who, according to Wikipedia, rejoiced in the full name of József Tihamér Antall de Dörgicse et Kisjene, and was from an ancient Hungarian family from the lower nobility. Antall duly became the MDF’s candidate for prime minister next spring, during the general elections which, following the dissolution of Parliament on March 16, 1990, were scheduled for March 25.

Of the more than 50 political parties and associations established prior to polling, 12 contested assembly seats at the national level. The most relevant among them were the MDF, the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ), the Independent Smallholders’ Party (FKGP, which had roots going back to inter-war years) and the Hungarian Socialist Party (the MSZP, basically the larger reform wing of the old MSZMP; the hardliners formed the Hungarian Workers’ Party, or MMP, which still exists today but is an electoral irrelevance and has never won a seat in parliament).

József Antall, Jr. with his two sons, György and Péter at Kékes in 1970. From the Antall-család archívum (Antall family archives).

The 1st Government

The first round of polling on March 25 ended with only five definite results in the 176 local constituencies. Six parties participated in the run-off elections of April 8; the MSZP ran alone, but the SZDSZ allied with their fellow liberals the League of Young Democrats (FIDESZ), while the MDF, agrarian Smallholders and the Christian Democratic People’s Party (KDNP) formed an electoral pact.

Of these, MDF, led by Antall, emerged as the largest single party, taking 164 seats. A coalition government was formed by the above three parties and Antall became the prime minister of the first government after the regime change.

“The new Antall government wants to be the government of freedom, the government of the people, the government of economic turnaround, and a European government.” These were the four key principles laid out at the beginning of the party’s program speech that Antall delivered on May 22, one day before the formation of the government.

He also stated some of the qualities of governance as he and his party members envisioned them, including the avoidance of extremes, the tolerance, and the circumspect but committed pursuit of progress.

“The speech was very sober and realistic wherever it touched on such details,” author Gyula Kodolányi, the writer of many of Antall’s speeches said in an interview with the Hungarian Review. “Antall did not make empty promises then or on any other occasion. He thought that freedom and democracy and the regaining of national self-determination are our cardinal rewards, and the rest will depend on talent, perseverance and the international constellation,” added Kodolányi, who was the son-in-law of poet Gyula Illyés, and the son of novelist János Kodolányi.

Hungarian Prime Minister József Antall with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in Budapest, September 1990. From the Antall-család archívum (Antall family archives).

The 1st Prime Minister

The first prime minister of the country after the regime change was anything but a typical politician. He had the attitude and approach of the academic he was, with a unique vision. In an introduction to a book compiling Antall’s speeches, Géza Jeszenszky, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of his cabinet and also his brother-in-law, cites an obituary that describes Antall as “the unsung hero of transition in Central Europe whose vision, grasp of world affairs and performance were much appreciated by the political leaders of the early ’90s, but who was not given due recognition by the world press.”

In fact, Antall wasn’t popular with the foreign press at all: in a piece by the New York Times reporting on Antall’s death, the journalist called him a rather uncharismatic leader. “The Prime Minister of the first non-communist government represents a kind of legendary figure, the well-intentioned, decent, but old-fashioned, not too successful first leader following the regime change,” Jeszenszky writes. “But today even his former political opponents give belated recognition and praise for his personality and politics.”

While he may not have been a typical politician, politics were not foreign to Antall at all. His maternal grandfather was a deputy secretary of state. His father, József Antall Sr., a jurist and civil servant, was one of the founding members of the Smallholders’ Party, and served as Government Commissioner for refugee affairs between 1939 and 1944 and helped saved the lives a of tens of thousands of people, mostly Poles. He resigned when Nazi Germany invaded Hungary (by then looking for a way out of the war and its alliance with the Axis forces) and according to Wikipedia was even arrested by the Gestapo. He received official decorations from Britain, Poland and Israel after the war and continued to work for the government after 1945, but withdrew from politics after the Communist takeover in 1948.

Antall witnessed all these crucial moments of history and become an active part of it. During the 1956 revolution he was arrested several times and, while he escaped prison time, he was barred from the teaching profession and lost his job in a Budapest gimnázium (grammar school).

He found a job as a librarian and became the director of the Semmelweis Medical History Museum, 10 years after he joined it in 1964. He did not give up on history and politics either; along with many members of his later cabinet, he contributed to the formation and the strengthening of the opposition forces that led the country to the regime change.

When forming the government, Antall relied on the huge network of people he had built up throughout the years whose abilities he knew quite well. As Kodolányi put it, he carried around a personal encyclopedia in his head, containing the name, training, skills, character and family background of several thousand Hungarian intellectuals and professionals, of whom several hundred were personal acquaintances.

U.S. President George H. W. Bush with Hungarian Prime Minister József Antall in the White House garden in October 1990. Photograph was provided to the Antall family archives by the Bush Archives.

The Government in Action

Many praised him for being able to assemble a cabinet with like-minded people, which was challenging in an environment full of politicians of the previous regime. Others, however, criticized him for assigning teachers with political cabinets, whose abilities they consequently challenged.

The Antall government’s “performance”, too, has been highly debated ever since by both right-wing and left-wing forces. Depending on their inclination, they cite the lack of its firmness in general political questions or its grasp on economic issues.

What many fail to take into consideration is the heritage of the previous 40 or so years: the obvious economic and social difficulties, the enormous amount of state debt, the crippled industry or the loss of its major market, the Soviet Union.

These, together with a country that expected its new democratic political elite primarily to resolve economic difficulties and halt the deteriorating standard of living, soon led to dissatisfaction.

Tension rose as the economic difficulties became more apparent: in the first year of the Antall government, GDP fell by more than 10% and inflation was running as high as 35%. Probably the most memorable event during the Antall era was the taxi-blockade in the fall of 1990, a subject we will return to in this series in a later issue.

In the Parliament as well there were heated debates, many revolving around symbolic issues, for example the instruction of theology in schools. The government’s inexperience in the democratic political practice or the novelty of new legal framework also served a cause for criticism. There was a lot of friction within the coalition as well with the Smallholders Party taking a different approach in the questions or reparation (of lands), and eventually leaving the coalition altogether.

Despite the numerous negatives tied to his name, there were some highlight of his governance. It was thanks to Antall’s effective contribution that the Warsaw-pact and Comecon (the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, known in Hungary by the initials KGST) were abolished. It was during his time in office that the last Soviet soldier left Hungary in June 1991. Perhaps most importantly, he was able to ensure political stability in Hungary.

The Tomb of Antall József, by sculptor Miklós Melocco. Photo by hu:User:Ineptus

The Death of Antall

Antall and his government probably had little chance of being reelected but his party would have certainly done better in the 1994 elections had the prime minister lived to see that date, Jeszenszky writes. Soon after he took office, Antall was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a type of cancer of the lymph glands. Though he received chemotherapy treatment his condition did not improve. On December 12, 1993, he died at the age of 61.

His funeral began on December 18, at noon: his coffin was taken from where it had laid in state in the Dome Hall of Parliament to a bier erected in front of the building. Speaker György Szabad, writer András Sütő and Abbot Pál Bolberitz made the formal farewells. From here, the procession left for the National Burial Garden on Fiumei út, where Cardinal László Paskai, Primate Archbishop of Esztergom, Reformed Bishop Lóránt Hegedűs, Lutheran Bishop Béla Harmati, Chief Rabbi József Schweitzer and László Tőkés, Reformed Bishop of Oradea, all spoke.

Many foreign leaders attended the state service: U.S. Vice President Al Gore and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, President Lech Walesa of Poland, and many prime ministers and deputy prime ministers from the former Eastern Bloc and Europe.

His successor in the Prime Minister’s seat was his Minister of the Interior Péter Boross, but the 1994 parliamentary election saw the MDF suffer a serious defeat (it was never to be the same force again in politics) and, to the surprise of many, a win for the Socialist Party.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.