El Greco at the Museum of Fine Arts: Unexpectedly Transformative

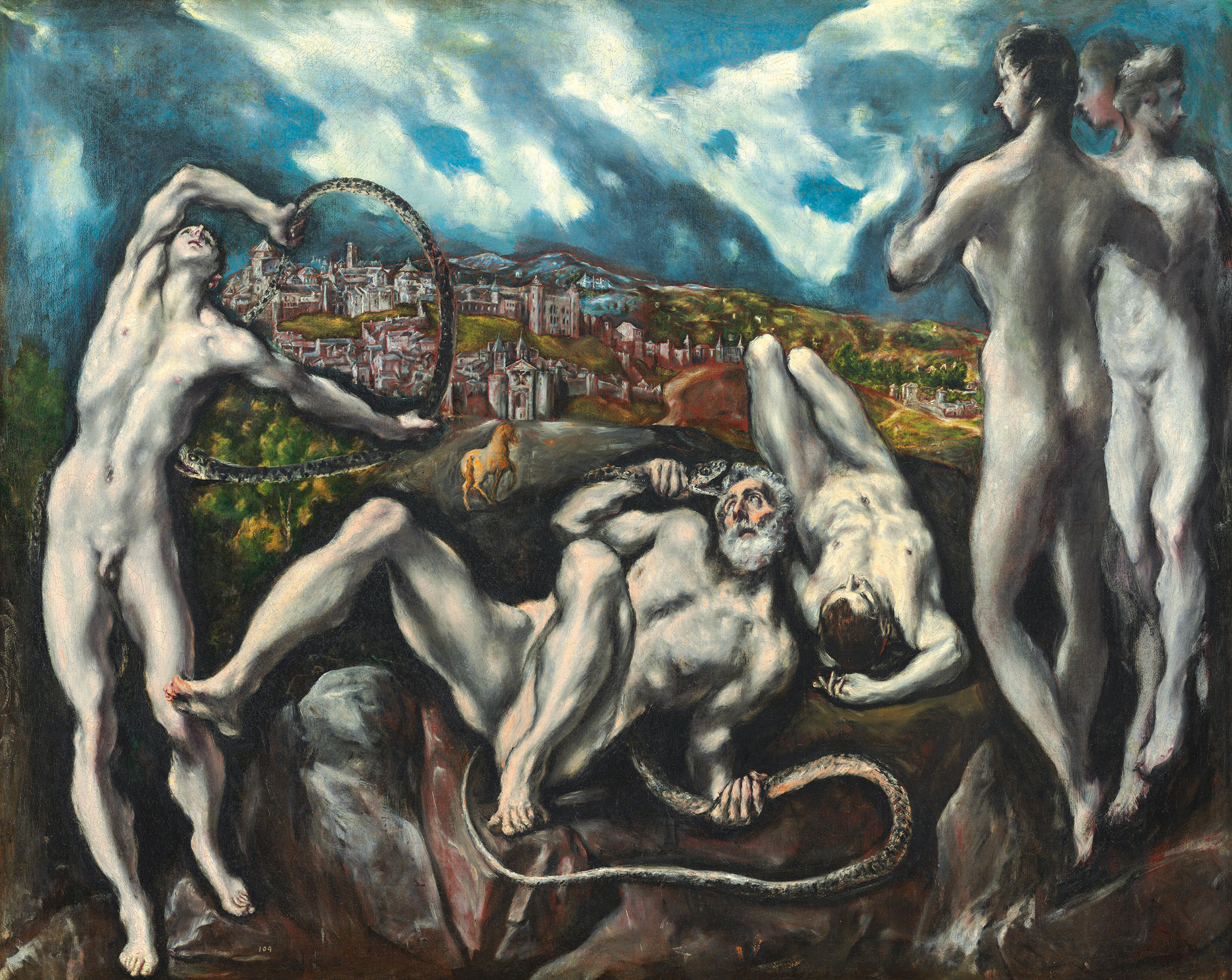

Trojan priest Laöcoon and his sons are killed by Minerva’s seas serpents ahead of the fall of Troy.

Walking up the steps to the entrance of the Museum of Fine Arts in Heroes Square to visit the El Greco exhibition, it struck me that I’ve seen more world-class public displays of work by great artists in Budapest than anywhere else in my life.

Exhibitions here tend to be smaller and come with less cultural snobbishness attached than elsewhere. You just go and see them. And you generally don’t have to wait for hours harrumphing at the backs of other people rather than in front of the painting you want to peruse.

The exhibition runs until mid-February 2023 and is the first comprehensive showing of El Greco’s work ever arranged in Budapest. This is somewhat surprising as the Museum of Fine Arts houses the highest number of what are called “autograph paintings” by El Greco outside Spain.

An autograph painting is one believed to have been painted entirely by the artist without the help of assistants.

Alongside works from the museum’s collection, those on display were loaned by more than 40 private and public collections.

El Greco’s real name was Domenikos Theotokopoulos. He was born and grew up on Crete, the largest of the Greek islands. In 1541, the year he was born, it was part of the Venetian Republic.

After training as an icon painter, El Greco left Crete for Venice in 1568 to learn western painting. He arrived in Rome in 1570, where he studied the work of the great Renaissance artists Tintoretto and Titian. Although he stayed in Rome for seven years and opened a studio, El Greco didn’t win a single public commission. Declaring that Rome’s highly lauded Michelangelo didn’t know how to paint might have had something to do with this.

Embraced by Spain

Things went far better for El Greco when he got to Spain and arrived in Toledo in 1577. His nickname comes from this time: El Greco means “the Greek” in Spanish. The churchmen of the city admired his work, and he received many commissions from religious institutions in and around the city. Private individuals purchased the devotional images he painted, and his portraits were acclaimed. El Greco died in Toledo in 1614. His son took over his workshop.

The exhibition is divided into seven chronologically and thematically arranged sections and shows how El Greco incorporated Renaissance characteristics, particularly composition and perspective, into his art and made them his own.

His “Christ Driving the Money Changers from The Temple,” for example, is filled with swirling figures in motion, including that of Christ at the center. The city of Toledo, which fascinated El Greco, is glimpsed through an arch behind him, linking this biblically themed work to his milieu, perhaps to make a point.

Toledo features again in the stand-out strangest painting in the exhibition, “Laöcoon,” dated to 1610-1614.

The only known painting by El Greco to be based on a Classical myth, it depicts Laöcoon, the priest of Troy, and his two sons being killed by serpents sent by the goddess Minerva, as told in Virgil’s “Aeneid.” Laöcoon had recognized that the wooden horse delivered to Troy by the Greeks was a trick, not a gift, and begged the Trojans not to take it into the city. Minerva, her burning hatred fanned by the memory of Paris spurning her, wanted the Greeks to defeat the Trojans.

Despite Laöcoon’s warnings, the Trojans dragged the wooden horse into the city anyway, and the rest is history, or, at the very least, legend: The Greeks burst out of it and destroyed Troy.

As with El Greco’s religious paintings, you don’t need to know the story to appreciate the work, although there is a tiny wooden horse in the background, heading for Toledo, not Troy. What makes “Laöcoon” so powerful and strange is the way the soft and fleshy but oddly angular paleness of the nude human bodies contrasts with the jagged rocks on which they’re positioned and the roughly painted clouds looming over Toledo like phantoms.

Mad or Modern?

“Laöcoon” comes roughly midway through the exhibition. After that, I couldn’t help noticing that El Greco’s style became increasingly rough. This might have had something to do with his vitality and vision fading. It was also suggested by his contemporaries that he was descending into madness in his later years, but I don’t think so.

I’d say it’s more likely that El Greco was constantly exploring what painting could be. He was a painter who mastered the smooth, flatness of icon painting and the colors that went with it. During this time, he studied paint and how it behaved on different surfaces.

Once in Rome, he absorbed characteristics of Renaissance art such as composition, color, painting landscape and spatial representation as he learned to use oil on canvas. When he arrived in Toledo and became a mature painter, he put everything he’d learned into the service of large, dynamic works and portraits that possess a marked humanity and intensity.

It is this unrelenting exploration of painting as a medium that gives El Greco’s later work its peculiar modernity. His themes might have remained religious and, as such, of their time. But, by exploring space and form unceasingly in his later work, he’s more like a painter such as Picasso, who refuses to stay stuck within a particular style or genre.

The difference is, of course, that Picasso could give full rein to his obsessions. El Greco had to smuggle his in. Maybe this is also what makes the work so powerful.

Sitting in the lobby of the Museum of Fine Arts waiting for my partner, something about the light, the motion of the people in the space, their faces, and the way they moved across the checkerboard floor made me feel I was in an El Greco painting. No other artist’s work has ever had that effect on me.

Find out more about the El Greco exhibition at www.mfab.hu. Ticket prices range from HUF 1,900-4,200.

This article was first published in the Budapest Business Journal print issue of November 18, 2022.

SUPPORT THE BUDAPEST BUSINESS JOURNAL

Producing journalism that is worthy of the name is a costly business. For 27 years, the publishers, editors and reporters of the Budapest Business Journal have striven to bring you business news that works, information that you can trust, that is factual, accurate and presented without fear or favor.

Newspaper organizations across the globe have struggled to find a business model that allows them to continue to excel, without compromising their ability to perform. Most recently, some have experimented with the idea of involving their most important stakeholders, their readers.

We would like to offer that same opportunity to our readers. We would like to invite you to help us deliver the quality business journalism you require. Hit our Support the BBJ button and you can choose the how much and how often you send us your contributions.